The UHA blog is beginning a series on the Urban History Association’s past award winners, the process of creating the work and, in the case of the dissertation prize, turning it into a book. The first subject is Catherine McNeur, an assistant professor of environmental and public history at Portland State University. Her Yale dissertation won the UHA prize in 2012 and it is coming out as a book this fall with Harvard University Press. (Available through Amazon, HUP, and Portland institution Powell’s.)

How did you come to develop the two areas of specialization as a professor of environmental history and public history? And how do they work together in your current position?

Prior to beginning graduate school in history, I worked for several years in historic preservation in New York City. Once I began graduate school, however, I focused primarily on environmental history, urban history, and American history more generally. When I saw the position posted at Portland State for someone who specialized in both public and environmental history, I was eager to apply. Portland State has a thriving public history MA program that draws students from around the country, many of whom find positions in the region. I’ve been having fun developing public history courses with an environmental twist. This spring, for instance, I taught a course on historic preservation where we focused not only on the social, political, and architectural aspects of preservation, but also the environmental (heritage landscapes, superfund sites, and the adaptive reuse of buildings). I’m particularly excited about next spring when I’ll be partnering with the foresters at Portland’s Heritage Tree program to teach a public history laboratory course. We’ll be helping to bring attention to the program by researching the histories of the trees that have been saved, writing walking tours and brochures, and the like. Down the road I also hope to develop public history courses about environmental justice and the interpretation of superfund sites.

What was your path through graduate school to tenure track faculty? What elements of your scholarly and professional profile would you say were most valuable in securing your job?

I think a fair amount of luck is involved with securing a tenure-track job these days. For the position at Portland State, specifically, I think it helped that I had background in both public history and environmental history. Besides that, I can really only speculate on what helped. I had gone on the job market the year before I got the job at Portland State. While I didn’t secure a tenure-track position, I was fortunate to get the Schwartz Postdoctoral Fellowship at the New-York Historical Society and the New School. This gave me the chance to develop courses in urban environmental history and American food history and experience working with a range of different students. I also deliberately worked to secure a book contract soon after graduation and that may have helped with the process. It’s hard to say which ingredient was the most important but I certainly feel fortunate to be where I am.

Tell us about your research and how you developed the topic for your dissertation, which won the 2012 Best Dissertation Prize from the UHA.

Early on in graduate school, I took a research course with Joanne Freeman on the early republic. I was flirting with several possible topics but then had a fleeting memory of reading about New York City’s hog riots in Edwin G. Burrow and Mike Wallace’s Gotham. I found the idea of hogs on the streets of Manhattan amusing, as did my classmates when I floated this possible topic during discussion one day. My initial reaction that pigs were out of place in a city ended up fueling my larger project about how ideas of the urban environment and what properly belonged in a city changed over time. Unlike today’s enthusiasm over backyard chickens and rooftop beehives, the mid-nineteenth century saw a lot of backlash against urban agriculture. As I expanded the topic beyond pigs, I found some juicy stories about how various New Yorkers fought over the urban environment as they designed parks, sold horse manure to regional farmers, unearthed connections between corrupt politicians and corrupt food, developed shantytowns, and the like. By juxtaposing seemingly odd combinations of stories (excitement over using human waste as fertilizer alongside the development of Central Park, for instance), I was able to unearth larger themes about environmental justice, government power, and the transformation of nineteenth-century cities.

How did you balance the new, including stories about horse manure, with familiar topics like the development of Central Park? What was the process of developing this work — the scope, the stories, and the style? Who or what were your key influences? After graduating, what was your revision process like from dissertation to book?

Even seemingly familiar stories—such as the Draft Riots or the creation of Central Park—can turn out to be novel when placed in a new context, such as the long history of environmental injustices involved in transforming the urban environment. As I planned out this book, a major goal of mine was to never write off elite New Yorkers’ goals for beautification in favor of the goals of poorer New Yorkers. I wanted to maintain some sort of balance so both sides could be better understood. This meant I have topics that range from park development and the planting of street trees to shantytowns and the boiling of slaughterhouse waste.

I also knew going into this project that I wanted to work on the antebellum city, as both urban and environmental historians typically give the period less attention. Many of the issues facing cities in the Progressive Era were similarly playing out in the pre–Civil War city, although different players posed different solutions.

As I turned the dissertation into a book, my main goal was to make my arguments clearer, fine-tune the narrative, and tap into more of the literature on urban environments and public space. I can’t express enough how much I benefited from the peer reviews solicited by the university presses I shared the manuscript with. That process was one of the most fruitful I’ve experienced as a scholar so far and I look forward to paying that forward in the future.

Would you care to share any of those juicy stories to whet our appetites? And just how does one conceal a pig in one’s hoop skirt?

One of my favorite stories in the book comes from an offal contract scandal in the early 1850s. Following the cholera outbreak in 1849, City Inspector Alfred W. White was eager to remove a range of “nuisance industries” from areas near residences in Manhattan. Seeing how Irish and German immigrants were profiting from the recycling of slaughterhouse waste by boiling down its component parts and then both selling them to local manufacturers and feeding them to pigs, White had this idea to get into the business himself. He simultaneously made it illegal for these small-scale operators to do business, while setting up a company that would work exclusively with the city. He became a secret partner in a waste-recycling company that he founded. They initially set up an operation on South Brother Island—a little-known, uninhabited island that still exists, just south of Riker’s Island—where he and his partners would ship the waste, process what they could sell, and then feed the leftovers to thousands of pigs on the beach so that it could be washed away at high tide. Things started going wrong for this company quickly, though. One partner took over the steamship they were using to haul the barges of offal, blood, and bones, and used it to host parties with a “number of loose women and common prostitutes.” Apparently the boat became known as the “North River Brothel.” This story goes on, involving farmers in Queens and what’s now the Bronx calling their business a nuisance, and the contract eventually becoming exceptionally lucrative. Overall, though, it’s a story that allows me to delve into the growing municipal power over the urban environment, those who lost out in the process, and what the corruption meant for the variety of waste-related problems facing the city. And, plus it’s just plain entertaining to think of an offal boat being used for scandalous parties.

The story about pigs under hoopskirts comes from a different, but related incident. In this case, in 1859 the municipal government waged the “Piggery War” on the offal-boiling industries where there were penned pigs in what’s now midtown Manhattan. Journalists from a variety of newspapers followed along with the health inspectors and police as they toured the facilities and homes of the proprietors. The newspapers reveled in stories of Irish women hiding pigs in their homes, whether under their beds or in their dresser drawers, in hopes of tricking the police. The New York Herald specifically noted that it was a “pity the ladies in the locality do not dress in the prevailing fashion”—in other words hoopskirts—because they could have hid them there. In this period when bourgeois womanhood was so intricately tied to parlors and domesticity, the idea that dirty livestock were allowed into these homes reinforced the idea that the Irish immigrants were completely different from the middle-class readers of these newspapers. To top it off, they were so unfashionable that they couldn’t even use a hoopskirt to hide an extra hog.

What is next for you in terms of research?

I’m at this wonderful stage where I’m beginning to explore potential projects—small and large—that I might pursue. I’ve been so involved with the book project for the last few years that this summer is really my first chance to explore new topics in earnest. In general though, I’m looking to continue work in urban environments in the nineteenth century as well as ideas of environmental purity.

Catherine McNeur’s book Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City will be published this fall by Harvard University Press and is available for pre-order at Powell’s, Amazon, and Barnes and Noble. To learn more about her teaching and research, visit www.catherinemcneur.com.

Podcast Production

The Urban History Podcast has added a new member to the production team. Rachel Guberman is a grad student in history at the University of Pennsylvania. She formerly worked at NPR and WBUR. I asked Rachel to introduce herself so that people would know a bit more about who works on the podcast and what range of skills urban historians have and can develop.

The Urban History Podcast has added a new member to the production team. Rachel Guberman is a grad student in history at the University of Pennsylvania. She formerly worked at NPR and WBUR. I asked Rachel to introduce herself so that people would know a bit more about who works on the podcast and what range of skills urban historians have and can develop.I’ve always been interested in politics and inequality in the United States. Since my undergrad days at the University of Michigan, those interests have taken on a spatial cast, as I came to appreciate how race, class, and access are arranged across cities and suburbs, most often in systematic ways orchestrated in large part by public policy. I’ve continued to pursue these interests as a PhD candidate at the University of Pennsylvania, where I work with Tom Sugrue and Michael Katz. In 2013-14 I was the Penn Urban Studies Graduate Fellow, an opportunity which connected me with other scholars of urban and metropolitan issues across disciplines. I’m now finishing up my dissertation (which I’ll defend in the fall) and teaching in the undergraduate Urban Studies program.

My dissertation, “The Real Silent Majority: Denver and the Realignment of American Politics after the Sixties” grows out of these interests. Focusing on metropolitan Denver, it traces the emergence of a pragmatic,trans-partisan grassroots political sensibility from the late-1960s onwards that was overwhelmingly moderate, committed to personal choice and privacy, and organized around the mantra of “quality of life.” I then go a step further to show how this evolving grassroots politics got translated into formal politics, particularly through the Democratic Party. My story culminates in the election of Bill Clinton and the success of the Republican Contract with America, two seemingly polarized events that, I argue, were in fact both attempts to capture this volatile and rapidly expanding political center.

Before coming to grad school, I worked as a production and editorial assistant at National Public Radio in Washington and at WBUR, the Boston member station. While I hope that some of the investigative reporting and storytelling skills I developed as a journalist have carried over to my work as a historian, these days it’s rare that I get to make use of my audio production chops. That’s why I’m excited to be joining the Urban History podcast! It’s a great chance to bring together two of my very favorite things: history and radio. For the most part, I’ll be the one behind the scenes, cutting tape and making things flow. If I do my job right, you won’t even know I’m there.

2014 UHA Conference Program

Urban History Podcast #2, David Huyssen

In the latest episode of the Urban History Association Podcast, Andrew Needham and Lily Geismer talk to historian David Huyssen about his new book, Progressive Inequality: Rich and Poor in New York, 1890-1920. (HUP, Amazon, Powell’s). Huyssen (pronounced “HYOO-sen”) questions the notion of the Progressive Era as one inherently defined by progress. In a book featuring the messy specifics of individual lives, he examines points of interaction between people of different classes in New York. In the interview, he ultimately concludes inequality is a choice that society makes.

In the latest episode of the Urban History Association Podcast, Andrew Needham and Lily Geismer talk to historian David Huyssen about his new book, Progressive Inequality: Rich and Poor in New York, 1890-1920. (HUP, Amazon, Powell’s). Huyssen (pronounced “HYOO-sen”) questions the notion of the Progressive Era as one inherently defined by progress. In a book featuring the messy specifics of individual lives, he examines points of interaction between people of different classes in New York. In the interview, he ultimately concludes inequality is a choice that society makes.

You can stream from this site or follow the link and download the mp3. Follow the jump for notes on the interview.

Fifty Years of Get-Tough

Remembering Harlem and the Urban Street Justice of the 1960s Riots

A Guest Post by Alex Elkins

On July 16, 1964, shortly after 9:20 a.m., James Powell died on a sidewalk on East 76th Street, far from his native Bronx. He was 15 years old. Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan of the New York Police Department (NYPD) had shot the African American teenager three times, claiming that Powell had lunged at him with a knife. Powell’s peers insisted he had been unarmed. Either way, to the white owner of the apartment building where Powell died, who had sprayed African American teens with a garden hose and threatened them with racial taunts, and Gilligan, the white 17-year police veteran, Powell and his friends did not belong in the lily-white, wealthy Upper East Side. Indeed, they had acted on that presumption.

Word of Powell’s death soon drew 300 African American youth and 75 police officers into the area. The youth pelted the police with soda bottles. Some shouted, “This is worse than Mississippi,” and “Come on, shoot another nigger.” And so began, 50 years ago today, the Harlem Riot of 1964—the first of seven sizable African American uprisings that summer.

After six days, 465 arrests, more than one hundred injured, over $500,000 in property damage, and one death, the Harlem Riot finally came to an end. What did it mean? For African Americans? The police? Also: where did it come from? The 50-year anniversary presents an opportunity to reexamine the significance of the uprising in Harlem and other cities that summer and the more than 300 riots that rocked cities of every size across the country over the next three summers, comprising by far one of the most turbulent periods of urban rioting in United States history. Although Americans still think of the 1960s riots as many did at the time—the Civil Rights movement exploding in the North, the desperate cry of the marginalized inner-city poor—the roots of those events lay in a long War on Crime, in the history of big-city policing and urban community street justice.

The City as Text

A guest post by Michael Carriere.

I became an urban historian in no small part because I love cities. Since I was a child, I have been captivated by the sights, smells, and sounds of the urban environment. I’d like to think that this passion informs both my writing and my teaching on the subject of urban history, allowing readers and students alike to hopefully create their own attachments to cities. Yes, I am an historian, but the boundaries between past, present, and even future prove quite blurry when you’re dealing with something as alive and dynamic as the city.

Such a perspective does not mean that I’m a naïve optimist when it comes to the state of the city in the early twenty-first century. For the past ten years, I have lived in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a city that – like other Midwestern cities such as Detroit, Cleveland, and St. Louis – is often held up as a decaying model of “Rust-Belt” urban decline. Sadly, there is much truth in this depressing narrative of declension. I see the poverty, violence, and disinvestment that marks Milwaukee, as well as countless other American cities, on a daily basis. Through a variety of texts, guest speakers, and other teaching tools I try to impart to my students the history behind this present moment of crisis. That’s pretty much what I try to do with my writing as well.

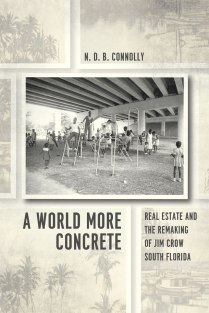

Hot Off the Presses: A World More Concrete by N.D.B. Connolly

N.B.D. Connolly’s much anticipated monograph on metropolitan Miami is finally out and available for pre-order. (Amazon, UChicago). Connolly wrote a popular response to Ta-Nehisi Coates‘ reparations article on this blog, and has been on television and radio of late, including WEAA Baltimore’s Marc Steiner show and WUNC’s The State of Things discussing redlining. Connolly is an assistant professor of history and co-director of the Racism, Immigration, and Citizenship Program at Johns Hopkins University.

From the author:

A World More Concrete: Real Estate and the Remaking of Jim Crow South Florida explores the history of real estate development and political power by offering an unprecedented look at the complexities of property ownership during the early and mid-twentieth century. The book argues that black and white property owners, in their various defenses of property rights, used Jim Crow segregation and other forms of white supremacy as instruments of economic growth and as core features of liberal governance. In Greater Miami as elsewhere, racially inflected urban redevelopment programs, segregated slum housing, “Whites Only” hotels, and other markers of Jim Crow’s built environment served as extensions of a political culture in which the better-off were always supposed to speak for the worse off, and where poor people, and especially poor black people, seemed most useful in generating other people’s wealth.

A World More Concrete: Real Estate and the Remaking of Jim Crow South Florida explores the history of real estate development and political power by offering an unprecedented look at the complexities of property ownership during the early and mid-twentieth century. The book argues that black and white property owners, in their various defenses of property rights, used Jim Crow segregation and other forms of white supremacy as instruments of economic growth and as core features of liberal governance. In Greater Miami as elsewhere, racially inflected urban redevelopment programs, segregated slum housing, “Whites Only” hotels, and other markers of Jim Crow’s built environment served as extensions of a political culture in which the better-off were always supposed to speak for the worse off, and where poor people, and especially poor black people, seemed most useful in generating other people’s wealth.

In the rich geography and diverse populations it renders, A World More Concrete affirms widely held beliefs that Greater Miami has always exhibited certain rare qualities, especially as it concerns the city’s Caribbean affinities. Yet, the book also explains how inhabitants of a seemingly exceptional city lived under a decidedly unexceptional political and pro-growth atmosphere – one that between the 1910s and 1960s reconciled apartheid with market practices and created more supple and, thus, more durable forms of racial segregation.

A World More Concrete makes two major contributions to the history of the twentieth-century United States and the wider Atlantic World. First, the book contends that it absolutely mattered that most civil rights leaders were also landlords and homeowners. Under the confines of American constitutional law, the activism of actual and aspiring black property owners ensured that the vocabulary of civil rights became synonymous with property rights. From the late nineteenth century on, in fact, black visions of equality depended less on inherently progressive or abstract communitarian ideals than on perceiving and strengthening an explicit link between citizenship, taxpayer rights, and the right to use violence in defense of private property. It’s A World More Concrete‘s focus on economic interests (rather than strict ideology) that enables the book to make its second major contribution: the desegregation of US political history. Capitalism, especially under Jim Crow, relied on a measure of interracial intimacy and collaboration that lubricated the flow of money and, at times, kept certain forms of government regulation at bay. Indeed, the book shows in no uncertain terms that the evolution of the American liberal state happened in direct concert with how effective people were at making money from and literally negotiating the color line decade upon decade.

Tell Us About Your New Book

We’re interested in keeping urban historians, the broader community of scholars, and the public informed about new and recent work in urban history. If you’ve got a book that is coming out or has just come out, send the bloggers a note and let us know.