By Pedro Regalado

Cross-posted at The Urban Opus

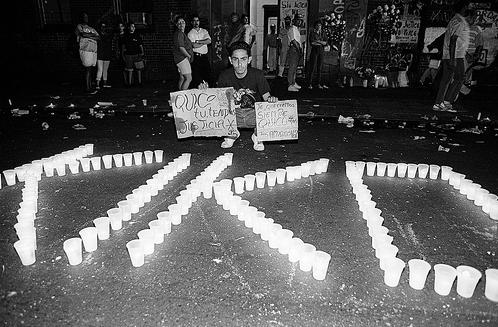

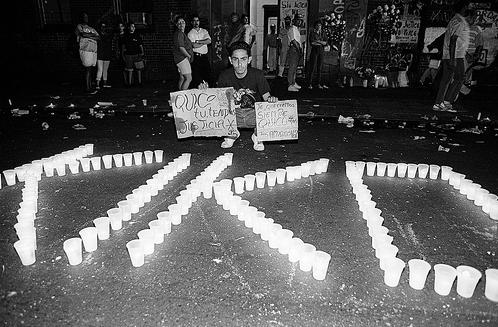

On the evening of July 3rd, 1992, a man of color died at the hands of white police. That night, plainclothes officer Michael O’Keefe and two other officers patrolled the lower section of New York City’s Washington Heights neighborhood, located just above Harlem beginning at 155th street. O’Keefe claimed to notice 23-year-old Jose “Kiko” Garcia carrying a weapon.[1] After an attempt to surround Garcia failed, O’Keefe pursued him.[2] Soon, the officers received radio cries from their distressed fellow officer. When they arrived at 505 West 162nd street, they found O’Keefe standing over a lifeless body.  This story has become a familiar one. Less than a day after Garcia’s death, Washington Heights erupted. Similar to the events that unfolded in Baltimore in recent weeks, outraged residents looted, desecrated storefronts, and set cars and buildings ablaze. They also marched and protested the police abuse that had too frequently affected residents both young and old. Like West Baltimore, Washington Heights symbolized the grim circumstances that urban communities of color faced then and now. Widespread poverty, high unemployment rates, deteriorating housing, underfunded schools, lack of social services, and high crime rates prevailed. For Washington Heights’ Dominican residents, police brutality, which often involved intimidation and personal invasion practices like frisking, only worsened matters. “You would come outside your apartment and they would frisk you[…]You would be dehumanized on a regular basis,“ remembered one resident.[3] In recent weeks, Baltimore’s African American residents have expressed similar sentiments.

This story has become a familiar one. Less than a day after Garcia’s death, Washington Heights erupted. Similar to the events that unfolded in Baltimore in recent weeks, outraged residents looted, desecrated storefronts, and set cars and buildings ablaze. They also marched and protested the police abuse that had too frequently affected residents both young and old. Like West Baltimore, Washington Heights symbolized the grim circumstances that urban communities of color faced then and now. Widespread poverty, high unemployment rates, deteriorating housing, underfunded schools, lack of social services, and high crime rates prevailed. For Washington Heights’ Dominican residents, police brutality, which often involved intimidation and personal invasion practices like frisking, only worsened matters. “You would come outside your apartment and they would frisk you[…]You would be dehumanized on a regular basis,“ remembered one resident.[3] In recent weeks, Baltimore’s African American residents have expressed similar sentiments.

As we witness Baltimore’s uprising develop, as rioters and protesters alike struggle to communicate their own disgust, part of our focus should attend not only to the underlying origins of the unrest — gracefully articulated by social critics the likes of Ta-Nehisi Coates — but to the larger structural effects of the upheaval locally and nationally. We should focus on the long-term political outcomes of the unrest equally as much as we attend to the immediate outcomes of the riots for Charm City’s African American residents. For among Washington Heights’ many lessons, the dual legacies of urban riots help us to see the possible future of urban policing in Baltimore.

Certainly, these two events and communities have their differences that make their respective uprisings unique. New York in 1992 is far different than Baltimore in 2015. However, a look back at the Washington Heights riots can help to reveal how uprisings function as social and political crossroads. It also elucidates the dangers of allowing right-wing political backlash to overtake the increased visibility of racialized urban poverty and violence.

Not long after the dust settled in Washington Heights, the neighborhood began to experience some of the changes that its residents sought when they rebelled on those warm summer days. In the years following the riots, Washington Heights became home to several new schools, increased representation in city government, new social services, and, perhaps most important, city-wide awareness of a working-class community that had previously been painted and treated as criminal by media and politicians alike. Community leader and councilman Gregorio Linares remembered, “We have gained tremendously from the experience of the disturbances…You can never say that something like this can never happen again…But this community is no longer what it was prior to the disturbances.”[4] He continued, “The reason this neighborhood did not go down in flames is because the community was able to respond quickly.”[5] Indeed, Dominican unity became a shining legacy of the Washington Heights riots for its community members whose common goal focused on the area’s peace as well as respect for its immigrant residents. However, their achievements, while significant, were limited as the visibility that the uprising created was soon manipulated for political ends entangled in New York City’s mayoral politics.

In September of 1992, two months after fires and rage adorned the hills of upper Manhattan, thousands of off-duty police officers had an uprising of their own. Beginning as a rally at City Hall Park organized by the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, off-duty police officers chanted “Dinkin’s must go!” and “No justice, No Police!” The officers lambasted then-Mayor David Dinkins for his treatment of police during the riots, including his visit to Garcia’s family days after the shooting, and also for his attempt to create an All Civilian Review Board that would investigate instances of police abuse and misconduct. Not unlike in recent months, city police felt threatened and their backlash was difficult to avoid.

In attendance was Republican mayoral candidate Rudolph Giuliani, who had lost the mayorship in a close race with Dinkins in 1989 and would run again in 1993. Giuliani stood high above the crowd during the rally and shouted, “The reason the morale of the New York Police Department is so low is one reason and one reason alone, David Dinkins!”[6] In a New York Times op-ed published just a month earlier, Giuliani had criticized Dinkins for his handling of not only the Washington Heights riots but also the Crown Heights riots in Brooklyn a year prior. He asserted that Dinkins ceded “to the forces of lawlessness,” he called the rioters “urban terrorists.”[7]

Indeed, much of Giuliani’s campaign relied on chastising Dinkins and appealing to the white ethnic working classes of the city. Certainly, the NYPD served as a perfect group for the former prosecutor to appeal to. And among others standing on stage with him in the midst of an increasingly fervent rally was police hero and Garcia’s slayer, Michael O’Keefe.[8] As the rally’s intensity grew, thousands of off-duty officers swarmed past barricades at City Hall, trampling cars and blocking traffic from the Brooklyn Bridge. 300 on-duty police officers did little to stop them.[9] “The 2 ½-hour PBA demonstration was punctuated with chants of ‘Rudy! Rudy!’” noted one news report.

On November 3rd, 1993 — partly riding on the fear that he fostered among the city’s white residents concerning both the Washington Heights and Crown Heights riots — Rudy Giuliani became the mayor of New York City and would serve as such into the 21st century. Despite losing Manhattan, the Bronx, and Brooklyn, Giuliani swept white ethnic strongholds in Staten Island and Queens, winning the mayorship by approximately three percent. Addressing his supporters at the New York Hilton Hotel just moments after his 1993 victory, Giuliani stated, “You know, nobody, no ethnic, religious or racial group will escape my care, my concern and my attention.” Through policing, the new mayor would make this certain.

Soon after taking office, the mayor appointed William Bratton as the city’s 38th Police Commissioner. With Giuliani’s backing, Bratton introduced Broken Windows policing in New York City. He also pioneered the use of CompStat, a police management tool rooted in statistics that sought to reduce the city’s severe crime rate. In tandem with Broken Windows, CompStat made police officers more accountable to statistical objectives that served political agendas than to the poor communities that they were intended to serve. They also placed considerable pressure on police officers to make arrests, which helped to increase cases of police abuse, summons, and stop and frisks throughout the city. While crime in New York dropped steadily and rents continued to increase in the years following Washington Heights’ uprising, New York’s poor residents benefitted little from reduced crime. Instead, they faced displacement to more impoverished and dangerous areas of the city.

As the 1990’s continued, both Broken Windows and CompStat’s negative implementations circulated throughout other major cities in the U.S. with similar socio-political landscapes and similar politicians facing high crime rates. Baltimore was no exception. In 1999, the city adopted CitiStat, modeled closely after Compstat. And in 2007, current Maryland governor and Democratic presidential hopeful Martin O’Malley, who instituted CitiStat as mayor, rebranded it as Maryland StateStat, widening the program’s scale.

As we reflect on Baltimore’s current tense situation, we must be reminded that while the uprising presents new possibilities for organizing and solidarity that may lead to local success, it also provides the opportunity for police and political backlash that threaten to take advantage of increased awareness of African American plight in Baltimore. Recent headlines include “Baltimore Proves the Need for ‘Broken Windows’ policing” in the New York Post and “The Underpolicing of Black America” in the The Wall Street Journal. The dual legacy of the Washington Heights riots of 1992, should remind us of the larger stakes of urban governance for Baltimore and, indeed, the nation. We are at a new crossroads; the future is unclear. And as the dust settles in the streets of West Baltimore, we must turn away from the type of policing that leaves underprivileged residents further estranged and our cities in ruins.

Pedro A. Regalado is a PhD student in American Studies at Yale University. He interests include twentieth-century urban history, race, politics, and immigration.

[1] Dennis Hevesi, “Upper Manhattan Block Erupts After a Man is Killed in Struggle with a Policeman,” The New York Times, July 5th, 2014.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Interview with Black.

[4] Garcilazo, “A Positive Legacy: Dominican Unity.”

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Rudolph W. Giuliani, Rumor and Justice in Washington Heights,” The New York Times, August 7, 1992.

[8] Ibid.

[9] James C. McKinley Jr, “Officer’s Rally and Dinkins is Their Target,” The New York Times, September 17, 1992.